Ord Brighideach

LADY OF THE PERPETUAL FLAME AND SACRED WELLS,WE SEEK YOU.

Stories Of Brighid

Art by Yuri Leitch

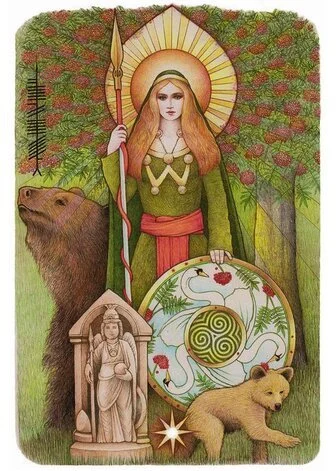

Brighid, daughter of the Dagda and the Morrígan, was born on the first day of February — the day that became sacred as Imbolc. At the moment of her birth, as the sun rose over the horizon, flames encircled her brow, marking her as a child of both fire and inspiration.

Because the Morrígan was not known for nurturing, the infant Brighid was suckled by a white, otherworldly cow with red ears. She was raised in the Otherworld, tending an apple orchard whose bees flew freely between this world and the next. From her earliest years, Brighid loved wisdom, learning, and inspiration.

In time, she founded a school at Kildare, where she tended a sacred grove. There she trained her followers for thirty years: the first ten spent in study, the second in service, and the last in teaching. They learned to gather healing herbs, tend livestock, and forge iron into tools.

Within her grove at Kildare stood an ancient oak, a healing well, and an everlasting flame. Nineteen women tended that flame, each keeping watch for a single day, while on the twentieth day Brighid herself was said to guard it. She was known to reward any offering, and so began the custom of casting coins into wells in her honor. Brighid was patroness of poets and musicians, lighting the fire of inspiration in their hearts. Some tales say she was wed to Senchán Torpéist, the great poet who preserved the Táin Bó Cúailnge.

Many healing wonders are attributed to her. It is told that two lepers once came seeking her aid. Brighid instructed them to bathe one another in her sacred well until they were healed. One obeyed, washing his companion until the sores vanished from his skin. But the man who was healed recoiled at the sight of the other’s illness and refused to touch him. When Brighid learned of this, she struck him again with leprosy, while the faithful one she wrapped in her mantle — and instantly he was made whole.

Brighid is also said to have consorted with Breas, the handsome but unjust king whose misrule led to the Second Battle of Moytura. Their son, Ruadán, was fostered among his mother’s kin, yet fought for his father’s Fomorian people. He sought to kill his uncle, Gobniu the Smith, but Gobniu struck back and Ruadán fell. At the death of her son, Brighid lifted her voice in the first keening. Her cry of grief was so piercing, so sorrowful, that it stilled the fury of battle, and warriors on both sides laid down their arms at the sound of her lament.

Brighid was worshipped especially in Leinster, invoked by warriors in battle and by women in childbirth. Midwives called upon her for aid, for she was guardian of women and newborns. Her healing cloak could spread wide enough to cover all of Ireland in times of need. It was said that on her festival of Imbolc, she stretched her mantle across the land to usher in the turning of the seasons, guiding winter toward spring.

On that day, people wove solar crosses of equal-armed design to honor her, symbols of her power to turn the wheel of the year. It was believed that the morning dew falling from her cloak carried healing. Rags or cloths left out to catch it became known as Brighid’s Mantle and could be laid upon the sick to soothe sore throats and other ailments.

Thus Brighid has long been honored as Goddess of fire and well, of poetry and healing, of childbirth and renewal. Whether known as saint or goddess, her presence continues to kindle inspiration, spread healing, and guard the turning of the year.

Brighid’s Cloak

In those days, the King of Leinster was not known for his generosity, and Brighid often struggled to persuade him to support her many charities. One day, when he was being especially tight-fisted, Brighid smiled and said:

“Well then, at least grant me as much land as my cloak can cover.”

Eager to be rid of her request, the king readily agreed. They were standing on the high ground of the Curragh, and Brighid directed four of her sisters to spread out her cloak. But instead of laying it flat upon the ground, each woman turned toward a different point of the compass and began to run.

To the king’s astonishment, the cloak stretched and grew as they ran, widening and widening across the plain. Other holy women joined them, grasping the edges to keep it in shape, until the cloak covered nearly a mile of land.

Alarmed, the king cried out,

“Oh, Brighid! What are you doing?”She answered calmly,

“It is not I, but my cloak, covering your province — for your stinginess to the poor.”

Terrified, the king quickly relented.

“Call back your maidens,” he begged. “You shall have good land, and I will be more generous in the future.”

Brighid drew back her sisters, and the cloak returned to its proper size. She received the promised acres, and from that day on, whenever the king grew tight with his purse-strings, she needed only to mention her cloak’s marvelous power to soften his heart.

Day Chapel Tapestry of the Church of the Annunciation, Clonard

Artwork by Wendy Andrews

Brighid and the Fox

A terrible mistake had been made. A man working in the woods mistook the King of Leinster’s tame fox for a wild one and killed it. When the King learned of the fox’s death, his grief was fierce. He ordered the man seized by his guards and thrown into prison.

The man’s wife, heartbroken, pleaded for mercy, insisting it had been an accident. But the King was unmoved.

“One death must be answered by another,”

he declared, and decreed that the prisoner should die.

Friends of the family, knowing Brighid’s compassion, begged her to intercede. Though Brighid honored the lives of animals, she knew the King’s judgment was unjust. She set out for the royal court to plead for the man’s life.

As she walked through the woodland, she prayed for guidance. Then, peering out from behind a tree, she saw a young fox — bright-eyed and curious. She called softly, and the fox trotted gladly into her arms. In that moment, Brighid understood what must be done.

Carrying the fox with her, she continued on to the King’s hall.

Still grieving, the King refused to listen to her pleas. His heart was set on vengeance. Then Brighid set the fox down before him and gently coaxed it to perform small tricks. To the astonishment of the court, the fox obeyed her joyfully — leaping, tumbling, and playing, just as the King’s beloved fox had once done.

Slowly, the King’s anger softened, replaced by wonder. It seemed as though this fox carried the spirit and skill of the one he had lost. His heart turned toward mercy. He pardoned the prisoner and restored him to his family. The King’s sorrow eased, and for a time he delighted in the new fox.

But one day, while the King rode out on business, the fox slipped away and vanished back into the woods. The King’s men searched long, but the creature was never seen again.

And so Brighid’s blessing brought life and mercy — for the man, his family, and for the fox, who returned to freedom in the wild.

The Story of Saint Brighid

Saint Brighid was born around AD 450 in Faughart, near Dundalk in County Louth. Her father, Dubhthach, was a pagan chieftain of Leinster, and her mother, Broicsech, was a Christian woman, said to have been born in Portugal. Like many in that era, Broicsech had been taken to Ireland through enslavement — a fate also shared by Saint Patrick.

Though Dubhthach was a man of wealth and standing, Brighid and her mother lived in service within his household. The child was named for the ancient goddess Brighid — patroness of fire, poetry, healing, and craft — whose presence was still deeply woven into the land and its people. From her earliest years, Brighid tended animals, prepared food, and cared for the needs of others.

She lived during the time of Saint Patrick and was deeply moved by his preaching. Inspired by the Christian faith, Brighid chose a life devoted to God through service to the poor, the sick, and the elderly. By the age of eighteen, she had left her father’s household, determined to walk her own path of devotion.

Her father urged her to marry, but Brighid refused. One story tells that she prayed her beauty would fade, so that no man would seek to claim her. Her prayer was answered, and her appearance changed — a sign of her resolve to belong only to her calling. Her generosity often angered her father, especially when she gave away his prized possessions to those in need. At last, he recognized that she was destined for religious life.

Brighid received the veil from Saint Macaille and vowed herself fully to God. After taking her vows, her beauty was said to return, brighter than before — a symbol of divine favor and spiritual radiance. Her wisdom and compassion soon became widely known, and women from across Ireland gathered to follow her way.

She founded many religious houses, the most renowned at Kildare, built beside a great oak tree — a place long held sacred. There, around the year 470, she established a double monastery for both women and men. As Abbess, Brighid held uncommon authority, governing with wisdom, justice, and care. The Abbey of Kildare grew into one of the most respected centers of learning and devotion in Christian Europe.

Brighid also founded a school of art at Kildare, where Saint Conleth oversaw metalwork, illumination, and craft. From this place emerged the legendary Book of Kildare, a work so beautiful that Gerald of Wales later claimed it seemed fashioned by angels rather than human hands.

Thus Saint Brighid stands as a bridge between worlds — honoring ancient wisdom while shaping a new spiritual tradition. Whether known as saint or goddess, her flame of compassion, creativity, and devotion continues to burn.

St. Brigid (1961) Gift of Mrs. Gayle Edwards Stain glass window in St. Mary Basilica

Artwork by Margaret McKenna

Brighid’s Cross

One of the oldest traditions in Ireland for welcoming the first stirrings of spring on February 1st — Brighid’s Day — is the weaving of her cross. Traditionally made from green rushes, which are pulled rather than cut, the crosses are woven by hand and hung above doorways or in the rafters to bless and protect the home.

According to custom, a new cross is made each year, and the old one is burned in the hearth. This act itself was believed to guard the house from fire. In many cottages, several crosses could be seen tucked into the ceiling, their older ones darkened by years of smoke. For people whose homes were thatched and built of wood, fire was both necessity and danger, and Brighid’s cross became a powerful symbol of protection, balance, and care.

Brighid and her cross are bound together through story as well as practice. One tradition tells that she once came to the bedside of a dying chieftain near Kildare. As she sat with him on the rush-strewn floor, speaking words of comfort, she began to weave the rushes into the shape of a cross.

The chieftain grew calm as he watched her hands at work. When he asked what she was making, Brighid explained the meaning of the cross and the faith it represented. As she spoke, his fear eased, and his heart softened. Whether understood as conversion, blessing, or simple presence at the threshold of death, the story binds the woven cross forever to Brighid’s compassion and care.

Brighid passed from this world around AD 525 and was buried at Kildare, the great center of her devotion. Over time, she came to be honored as one of the three patron figures of Ireland, alongside Patrick and Columcille. Her feast day on February 1st marks a turning point in the year — the moment when light begins to return and the land stirs toward spring.

Today, Brighid’s cross continues to be woven in homes across Ireland and beyond. Whether hung for protection, remembrance, or devotion, it remains a living sign of blessing — a reminder that care, shelter, and renewal begin at the hearth.