Stories of Our Beloved Brighid

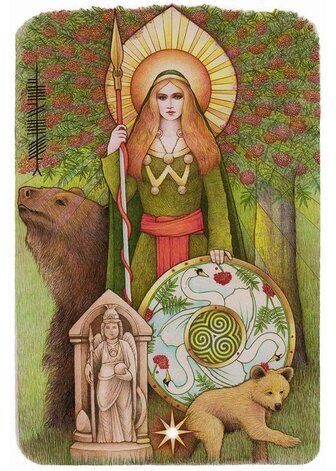

Art by Yuri Leitch

Art by Yuri Leitch

Daughter of the Daghda and the Morrigan the Goddess Brigid was born on the 1st day of February which became her sacred day of Imbolg. She was born with flames around her forehead just as the sun came over the horizon. Now the Morrigan not being the most nurturing of goddesses, the infant Brigid was suckled by another worldly cow, white, with red ears and grew up in the other world tending to an apple orchard whose bees moved between this world and the other world. Brigid loved learning, knowledge and inspiration and she set up a school of sorts in Kildare where she tended to a sacred grove. Her followers were instructed for ten years and she taught them how to gather healing herbs and tend to livestock, how to forge iron into tools. They would spend thirty years in service to her, the first ten years in learning, the second ten years in tending to her sacred grove and working and the final ten years in teaching.

There was an ancient oak tree in her grove in Kildare as well as a healing well and a sacred flame. Nineteen of her followers, all women, tended this flame. Each one had to watch over it for a day not letting it go out and on the 20th day, Brigid herself would tend to this everlasting flame. She was said to reward any offering to her so people started the custom of throwing coins into wells to honour her. She lit the fire of inspiration in the hearts of poets and musicians and is said to have been married to Senchán Torpéist, the author of the Tain Bo Cuainge.

One day two lepers came to her for healing and she told them to bathe each other in her sacred well until their sores were gone. The first leper bathed his companion faithfully and the sores fell away from his skin until he was completely healed. But when the healed man looked at his fellow, he felt such revulsion that he could not bring himself to touch the other even to bathe him. When Brigid found out that he hadn’t held up his end of the bargain, she was furious and she struck him down with leprosy again. She then wrapped the other leper in her mantle and his disease was gone from him in an instant.

She was said to have consorted with Breas, the handsome young king whose misrule lead to the second battle of Moytura. They had a son together called Ruadhan who grew up to be a great warrior and fought with his father’s Formorians against his mother’s people in the battle. Ruadhan tried to kill his uncle, Gobniu, the Smyth, but the craftsman struck a blow against Ruadhan who died instead. When her son fell, Brigid made the first keening over his body, the sound was so loud and so sorrowful that it took the battle fury out of all that were still fighting and they lay down their arms at the sound of it.

Brigid was worshipped as the Goddess of Leinster and invoked by Leinster men when they went into Battle. She was especially invoked by midwives, being associated with women, healing and childbirth. Her healing cloak could expand in size as needed and she could spread it all over Ireland in times of need. She was said to spread her cloak over Ireland at her festival day of Imbolg on the 1st February to usher in the change of seasons and turn winter into spring. Solar crosses with four arms equal in length were woven on Imbolg to honour Brigid’s role in changing the four seasons and were kept in people’s houses to invoke the goddess’s protection. The first dew of the morning fell from her cloak on that day and any rag left out to catch it would be infused with Brigid’s healing and could be laid on a sick person for the curing of sore throats and other ailments.

Source: Bard Mythologies

There was an ancient oak tree in her grove in Kildare as well as a healing well and a sacred flame. Nineteen of her followers, all women, tended this flame. Each one had to watch over it for a day not letting it go out and on the 20th day, Brigid herself would tend to this everlasting flame. She was said to reward any offering to her so people started the custom of throwing coins into wells to honour her. She lit the fire of inspiration in the hearts of poets and musicians and is said to have been married to Senchán Torpéist, the author of the Tain Bo Cuainge.

One day two lepers came to her for healing and she told them to bathe each other in her sacred well until their sores were gone. The first leper bathed his companion faithfully and the sores fell away from his skin until he was completely healed. But when the healed man looked at his fellow, he felt such revulsion that he could not bring himself to touch the other even to bathe him. When Brigid found out that he hadn’t held up his end of the bargain, she was furious and she struck him down with leprosy again. She then wrapped the other leper in her mantle and his disease was gone from him in an instant.

She was said to have consorted with Breas, the handsome young king whose misrule lead to the second battle of Moytura. They had a son together called Ruadhan who grew up to be a great warrior and fought with his father’s Formorians against his mother’s people in the battle. Ruadhan tried to kill his uncle, Gobniu, the Smyth, but the craftsman struck a blow against Ruadhan who died instead. When her son fell, Brigid made the first keening over his body, the sound was so loud and so sorrowful that it took the battle fury out of all that were still fighting and they lay down their arms at the sound of it.

Brigid was worshipped as the Goddess of Leinster and invoked by Leinster men when they went into Battle. She was especially invoked by midwives, being associated with women, healing and childbirth. Her healing cloak could expand in size as needed and she could spread it all over Ireland in times of need. She was said to spread her cloak over Ireland at her festival day of Imbolg on the 1st February to usher in the change of seasons and turn winter into spring. Solar crosses with four arms equal in length were woven on Imbolg to honour Brigid’s role in changing the four seasons and were kept in people’s houses to invoke the goddess’s protection. The first dew of the morning fell from her cloak on that day and any rag left out to catch it would be infused with Brigid’s healing and could be laid on a sick person for the curing of sore throats and other ailments.

Source: Bard Mythologies

ST. BRIGID'S CLOAK

Day Chapel Tapestry of the Church of the Annunciation, Clonard

Day Chapel Tapestry of the Church of the Annunciation, Clonard

The King of Leinster at that time was not particularly generous, and St. Brigid found it not easy to make him contribute in a respectable fashion to her many charities. One day when he proved more than usually niggardly, she at last said, as it were in jest: "Well, at least grant me as much land as I can cover with my cloak;" and to get rid of her importunity he consented.

They were at the time standing on the highest point of ground of the Curragh, and she directed four of her sisters to spread out the cloak preparatory to her taking possession. They accordingly took up the garment, but instead of laying it flat on the turf, each virgin, with face turned to a different point of the compass, began to run swiftly, the cloth expanding at their wish in all directions. Other pious ladies, as the border enlarged, seized portions of it to preserve something of a circular shape, and the elastic extension continued till the breadth was a mile at least. "Oh, St. Brigid!" said the frighted king, "what are you about?" "I am, or rather my cloak is about covering your whole province to punish you for your stinginess to the poor." "Oh, come, come, this won't do. Call your maidens back. I will give you a decent plot of ground, and be more liberal for the future." The saint was easily persuaded. She obtained some acres, and if the king held his purse-strings tight on any future occasion she had only to allude to her cloak's India-rubber qualities to bring him to reasons Source: Sacred-Texts.com

They were at the time standing on the highest point of ground of the Curragh, and she directed four of her sisters to spread out the cloak preparatory to her taking possession. They accordingly took up the garment, but instead of laying it flat on the turf, each virgin, with face turned to a different point of the compass, began to run swiftly, the cloth expanding at their wish in all directions. Other pious ladies, as the border enlarged, seized portions of it to preserve something of a circular shape, and the elastic extension continued till the breadth was a mile at least. "Oh, St. Brigid!" said the frighted king, "what are you about?" "I am, or rather my cloak is about covering your whole province to punish you for your stinginess to the poor." "Oh, come, come, this won't do. Call your maidens back. I will give you a decent plot of ground, and be more liberal for the future." The saint was easily persuaded. She obtained some acres, and if the king held his purse-strings tight on any future occasion she had only to allude to her cloak's India-rubber qualities to bring him to reasons Source: Sacred-Texts.com

Story of St. Brigid

St. Brigid (1961)

Gift of Mrs. Gayle Edwards

Stain glass window in St. Mary Basilica

St. Brigid (1961)

Gift of Mrs. Gayle Edwards

Stain glass window in St. Mary Basilica

St. Brigid was born in AD 450 in Faughart, near Dundalk in Co. Louth. Her father, Dubhthach, was a pagan chieftain of Leinster and her mother, Broicsech, was a Christian. It was thought that Brigid’s mother was born in Portugal but was kidnapped by Irish pirates and brought to Ireland to work as a slave, just like St. Patrick was. Brigid’s father named her after one of the most powerful goddesses of the pagan religion - the goddess of fire, whose manifestations were song, craftsmanship, and poetry, which the Irish considered the flame of knowledge. He kept Brigid and her mother as slaves even though he was a wealthy man. Brigid spent her earlier life cooking, cleaning, washing and feeding the animals on her father’s farm.

She lived during the time of St.Patrick and was inspired by his preachings and she became a Christian. When Brigid turned eighteen, she stopped working for her father. Brigid’s father wanted her to find a husband but Brigid had decided that she would spend her life working for God by looking after poor, sick and elderly people. Legend says that she prayed that her beauty would be taken away from her so no one would seek her hand in marriage; her prayer was granted. Brigid’s charity angered her father because he thought she was being too generous to the poor. When she finally gave away his jewel-encrusted sword to a leper, her father realised that she would be best suited to the religious life. Brigid finally got her wish and entered the convent. She received her veil from St. Macaille and made her vows to dedicate her life to God. Legend also says that Brigid regained her beauty after making her vows and that God made her more beautiful than ever. News of Brigid’s good works spread and soon many young girls from all over the country joined her in the convent. Brigid founded many convents all over Ireland; the most famous one was in Co. Kildare. It is said that this convent was built beside an oak tree where the town of Kildare now stands. Around 470 she also founded a double monastery, for nuns and monks, in Kildare. As Abbess of this foundation she wielded considerable power, but was a very wise and prudent superior. The Abbey of Kildare became one of the most prestigious monasteries in Ireland, and was famous throughout Christian Europe.

St. Brigid also founded a school of art, including metal work and illumination, over which St. Conleth presided. In the scriptorium of the monastery, the famous illuminated manuscript the Book of Kildare was created.

She lived during the time of St.Patrick and was inspired by his preachings and she became a Christian. When Brigid turned eighteen, she stopped working for her father. Brigid’s father wanted her to find a husband but Brigid had decided that she would spend her life working for God by looking after poor, sick and elderly people. Legend says that she prayed that her beauty would be taken away from her so no one would seek her hand in marriage; her prayer was granted. Brigid’s charity angered her father because he thought she was being too generous to the poor. When she finally gave away his jewel-encrusted sword to a leper, her father realised that she would be best suited to the religious life. Brigid finally got her wish and entered the convent. She received her veil from St. Macaille and made her vows to dedicate her life to God. Legend also says that Brigid regained her beauty after making her vows and that God made her more beautiful than ever. News of Brigid’s good works spread and soon many young girls from all over the country joined her in the convent. Brigid founded many convents all over Ireland; the most famous one was in Co. Kildare. It is said that this convent was built beside an oak tree where the town of Kildare now stands. Around 470 she also founded a double monastery, for nuns and monks, in Kildare. As Abbess of this foundation she wielded considerable power, but was a very wise and prudent superior. The Abbey of Kildare became one of the most prestigious monasteries in Ireland, and was famous throughout Christian Europe.

St. Brigid also founded a school of art, including metal work and illumination, over which St. Conleth presided. In the scriptorium of the monastery, the famous illuminated manuscript the Book of Kildare was created.

St. Brigid's Cross

St. Brigid of Kildare Stained Glass (photo by Fran McColman), St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, Macon, GA.

St. Brigid of Kildare Stained Glass (photo by Fran McColman), St. Joseph’s Catholic Church, Macon, GA.

Making a St. Brigid's cross is one of the traditional rituals in Ireland to celebrate the beginning of early spring, 1st February. The crosses are made of rushes that are pulled rather than cut. They are hung by the door and in the rafters to protect the house from fire and evil. According to tradition a new cross is made each St. Brigid's Day, and the old one is burned to keep fire from the house. Many homes have several crosses preserved in the ceiling the oldest blackened by many years of hearth fires. Some believe that keeping a cross in the ceiling or roof is a good way to preserve the home from fire which was always a major threat in houses with thatch and wood roofs. St. Brigid and her cross are linked together by the story that she wove this form of cross at the death bed of either her father or a pagan lord, who upon hearing what the cross meant, asked to be baptized.

One version goes as follows: "A pagan chieftain from the neighborhood of Kildare was dying. Christians in his household sent for Brigid to talk to him about Christ. When she arrived the chieftain was raving. As it was impossible to instruct this delirious man, hopes for his conversion seemed doubtful. Brigid sat down at this bedside and began consoling him. As was customary, the dirt floor was strewn with rushes both for warmth and cleanliness. Brigid stooped down and started to weave them into a cross, fastening the points together. The sick man asked what she was doing. She began to explain the cross, and as she talked his delirium quieted and he questioned her with growing interest. Through her weaving, he converted and was baptized at the point of death. Since then the cross of rushes has been venerated in Ireland."

St. Brigid died in AD 525 at the age of 75 and was buried in a tomb before the High Altar of her Abbey church. After some time, her remains were exhumed and transferred to Downpatrick to rest with the two other patron saints of Ireland, St. Patrick and St. Columcille. Her skull was extracted and brought to Lisbon, Portugal by two Irish noblemen, and it remains there to this day. St. Brigid is the female patron saint of Ireland. She is also known as the Muire na Gael or Mary of the Gael, which means Our Lady of the Irish. Her feast day is the 1st of February which is the first day of Spring in Ireland.

Source: ST. BRIGID'S GNS, GLASNEVIN

One version goes as follows: "A pagan chieftain from the neighborhood of Kildare was dying. Christians in his household sent for Brigid to talk to him about Christ. When she arrived the chieftain was raving. As it was impossible to instruct this delirious man, hopes for his conversion seemed doubtful. Brigid sat down at this bedside and began consoling him. As was customary, the dirt floor was strewn with rushes both for warmth and cleanliness. Brigid stooped down and started to weave them into a cross, fastening the points together. The sick man asked what she was doing. She began to explain the cross, and as she talked his delirium quieted and he questioned her with growing interest. Through her weaving, he converted and was baptized at the point of death. Since then the cross of rushes has been venerated in Ireland."

St. Brigid died in AD 525 at the age of 75 and was buried in a tomb before the High Altar of her Abbey church. After some time, her remains were exhumed and transferred to Downpatrick to rest with the two other patron saints of Ireland, St. Patrick and St. Columcille. Her skull was extracted and brought to Lisbon, Portugal by two Irish noblemen, and it remains there to this day. St. Brigid is the female patron saint of Ireland. She is also known as the Muire na Gael or Mary of the Gael, which means Our Lady of the Irish. Her feast day is the 1st of February which is the first day of Spring in Ireland.

Source: ST. BRIGID'S GNS, GLASNEVIN

Brigid and the FoxThe worst had happened. A man, working in the woods, saw a fox and killed it. Big error. It was the King of Leinster's pet fox not a wild one. The man was captured by the King's guard and imprisoned. His distraught wife begged for clemency and forgiveness for her husband as it was a genuine mistake. Unfortunately the King was too distressed at losing his fox and not disposed to release the man. In fact, as there had been one death it should be avenged by the death of the prisoner.

Friends of the family asked Brigid to intervene. Now Brigid, however much she valued the lives of animals, thought that the King's intentions were unjust and she set out for the Court to plead the case. As she journeyed she took a path through a woodland. It was narrow and she walked along carefully, trying to compose her speech to the King. She prayed for the right words and guidance. As if in answer to her prayers, low and behold, she noticed, looking at her from behind a tree trunk, a young fox. She called to it and the cub happily trotted over to her. An idea came to her mind and she took up the fox, and it joined in the journey to the castle. On arrival the King was not willing to pay heed to her protests and requests for the release of the killer. His pain at the loss of his fox was great and he wanted the death penalty. Brigid played her last card, the fox. She brought it out and started asking it to do tricks for the King and courtiers. It loved to do this for her and soon the coldest hearts were melted by its antics. Amazingly this new fox could do all the tricks that the King had taught his own pet. Slowly the bereaved man's displeasure eased and he finally relented and granted the prisoner a pardon. His joy with the new pet was great as he filled his days in pleasure at its games. However, the day came when the King had to leave on business. The fox took no time in escaping back to the wood. The King's men sent out search parties for the animal but it was never seen again. |

|